Edison Motion Picture Equipment Chronology

This chronology is not intended to be a definitive record of the dates of production or modifications made during the production runs of the various motion picture machines made by Thomas Alva Edison. It is only an overview of the basic models and major changes, with as many landmark dates as are well documented. The greatest accomplishment of this chronology would be to inspire more advanced research by future Cinequiptologists in order to produce a better record of the evolution of the Technology of the Moving Image.

These technological advancements would eventually lead to the home theater projectors we know today.

Kinetoscope - 1894

On Saturday, April 14th, 1894, the Holland Brothers opened their original Kinetoscope Parlor at 1155 Broadway in New York City and for the first time, commercially exhibited movies as we know them today. The patrons paid twenty-five cents for a ticket to see five of the ten machines that were set up in two rows. Each machine had a different film and only one customer could use a machine at any given time. Soon Kinetoscope Parlors sprang up in many towns across the country, often as part of Phonograph Parlors that were already in operation. Peter Bacigalupi brought San Francisco its first look at moving pictures with five Kinetoscopes that premiered on June 1st, 1894.

On Saturday, April 14th, 1894, the Holland Brothers opened their original Kinetoscope Parlor at 1155 Broadway in New York City and for the first time, commercially exhibited movies as we know them today. The patrons paid twenty-five cents for a ticket to see five of the ten machines that were set up in two rows. Each machine had a different film and only one customer could use a machine at any given time. Soon Kinetoscope Parlors sprang up in many towns across the country, often as part of Phonograph Parlors that were already in operation. Peter Bacigalupi brought San Francisco its first look at moving pictures with five Kinetoscopes that premiered on June 1st, 1894.

As mentioned, only one customer could use a Kinetoscope at any one time because the films were lit from behind and not projected, but were seen through a special magnifying glass. An electric motor ran the mechanism that moved the film in a constant motion past the shutter, rather than using an intermittent movement, which is necessary for a movie projector.

The films themselves were less than a minute in length and were stored in an endless loop on a spoolbank, so that there was no delay to rewind them between showings.

Kinetophone - 1895

Edison experimented with synchronizing sound and film using his cylinder phonograph. In 1895 he sold a few Kinetoscopes with sound attachments, which played a record that was not synchronized through ear-tubes during the film. These devices were called Kinetophones and that name was used again in 1913 to describe the projectors used to show Edison's "Talking Pictures".

Edison experimented with synchronizing sound and film using his cylinder phonograph. In 1895 he sold a few Kinetoscopes with sound attachments, which played a record that was not synchronized through ear-tubes during the film. These devices were called Kinetophones and that name was used again in 1913 to describe the projectors used to show Edison's "Talking Pictures".

Vitascope - 1896

The Vitascope opened at Koster and Bial's Music Hall in New York City on

The Vitascope opened at Koster and Bial's Music Hall in New York City on  April 23rd, 1896 and although Thomas Armat was the real inventor, credit was given to Edison in order to promote the new invention.

April 23rd, 1896 and although Thomas Armat was the real inventor, credit was given to Edison in order to promote the new invention.

Edison was in the audience the night of the opening along with William Reed, who was a projectionist or "electrician" and would tour with the first Vitascope show in the south. This program is from a show at the Grand Opera House in Meridian, Mississippi, in February of 1897 when William Reed was the projectionist. Vitascope and other early shows had a lot of problems with electrical current that wasn't standardized across the country, and the man who ran the machinery was billed as the "electrician", a term that replaced "lanternist" before "projectionist" was adopted.

The Vitascope used a spoolbank like the Kinetoscope and could repeat the short films of such scenes as the surf coming in, trains arriving at the station, or "Feeding the Doves". This was different than the way films were handled in Europe where they were simply allowed to fall into a basket or box on the floor, and which they sometimes missed. Since the films were made of nitrate, this created quite a fire hazard and was what was blamed for the Charity Bazaar fire in Paris that claimed 124 lives. As an example of how quickly interest in the movies was spreading, a report of the Charity Bazaar fire made the newspaper in the tiny town of Hillsboro, New Mexico in September of 1897.

Projectoscope - 1897

After breaking with Armat and his Vitascope, Edison came up with what was truly his own machine and called it the Projectoscope. Projectoscopes first used a spoolbank identical to what was inside the Kinetoscope, but later went to a crude reel system for supply and take-up. They also incorporated a Magic Lantern attachment for still slides by 1898. Projectoscopes were used by early itinerant showmen such as CL White, who showed the first movies in Arizona in 1897-98, as well as the 1897 Ringling Brothers Circus. One New England Showman renamed his Projectoscope the "War-O-Scope" when he showed recreated movies of the Spanish-American War.

After breaking with Armat and his Vitascope, Edison came up with what was truly his own machine and called it the Projectoscope. Projectoscopes first used a spoolbank identical to what was inside the Kinetoscope, but later went to a crude reel system for supply and take-up. They also incorporated a Magic Lantern attachment for still slides by 1898. Projectoscopes were used by early itinerant showmen such as CL White, who showed the first movies in Arizona in 1897-98, as well as the 1897 Ringling Brothers Circus. One New England Showman renamed his Projectoscope the "War-O-Scope" when he showed recreated movies of the Spanish-American War.

Projecting Kinetoscope - ca.1901

Edwin S Porter was one of the men who ran Vitascope machines, and his skill as a mechanic was appreciated by Edison, who hired him to improve his cameras and what were now called "Projecting Kinetoscopes". Note the similarities of the lamphouse, Magic Lantern attachment and tall case between this very early Projecting Kinetoscope and the Projectoscope. The difference is the gear train designed by Porter and which was used with modifications in all commercial machines up until the last model.

Edwin S Porter was one of the men who ran Vitascope machines, and his skill as a mechanic was appreciated by Edison, who hired him to improve his cameras and what were now called "Projecting Kinetoscopes". Note the similarities of the lamphouse, Magic Lantern attachment and tall case between this very early Projecting Kinetoscope and the Projectoscope. The difference is the gear train designed by Porter and which was used with modifications in all commercial machines up until the last model.

Universal Projecting Kinetoscope - 1904

The Universal Model Projecting Kinetoscope was built for the semi-professional or the showman who was just getting started in the movie business. They were light weight machines and sold as either complete outfits or as projection heads only which could be adapted to a showman's existing Magic Lantern. This 1904 ad from the Klein Optical Co of Chicago shows a Universal being used with a Biunial Magic Lantern with limelight burners and which sold for $220 as an outfit.

The Universal Model Projecting Kinetoscope was built for the semi-professional or the showman who was just getting started in the movie business. They were light weight machines and sold as either complete outfits or as projection heads only which could be adapted to a showman's existing Magic Lantern. This 1904 ad from the Klein Optical Co of Chicago shows a Universal being used with a Biunial Magic Lantern with limelight burners and which sold for $220 as an outfit.

Exhibition Projecting Kinetoscope - 1904

Another 1904 Klein Optical Co ad was selling this Exhibition Model Projecting Kinetoscope for $115. The arc lamp would have been preferred over the limelight by the showmen who were opening Nickelodeon theaters all across the country. The reels were still exposed at this time and the take-up was gear driven with a clutch. There was an idler roller and a device to rewind film built into the machine and the intermittent movement was a two pin style.

Another 1904 Klein Optical Co ad was selling this Exhibition Model Projecting Kinetoscope for $115. The arc lamp would have been preferred over the limelight by the showmen who were opening Nickelodeon theaters all across the country. The reels were still exposed at this time and the take-up was gear driven with a clutch. There was an idler roller and a device to rewind film built into the machine and the intermittent movement was a two pin style.

Improved Exhibition Model - 1910

Local fire laws required magazines for nitrate film beginning in 1907, as well as fire safety doors that blocked the light from the film if the projector ran too slowly. Exhibition Model projecting mechanisms were basically unchanged from Porter's 1901 version, however this Improved Exhibition Model and later machines had a single pin rather than a two pin intermittent movement. The new additions of belt drive take-up, film magazines and improved arc lamp raised the price of this outfit to $155 without the optional fire door. This illustration is from a 1910 Edison Kinetoscope Catalog.

Local fire laws required magazines for nitrate film beginning in 1907, as well as fire safety doors that blocked the light from the film if the projector ran too slowly. Exhibition Model projecting mechanisms were basically unchanged from Porter's 1901 version, however this Improved Exhibition Model and later machines had a single pin rather than a two pin intermittent movement. The new additions of belt drive take-up, film magazines and improved arc lamp raised the price of this outfit to $155 without the optional fire door. This illustration is from a 1910 Edison Kinetoscope Catalog.

Underwriters Model, Type "B" - 1912

Both Exhibition and Underwriters Models were in production at the same time, with the Underwriters Model using a nickel-plated cast iron body versus the finger jointed oak case of the Exhibition Model. Late issue Exhibition machines and all Underwriters Models carried the nameplate and a license number of the Motion Picture Patents Company. The big difference between the two models is the use of a front shutter on all the later Underwriters machines. This front shutter made it necessary to mount the lower magazine underneath the base board, rather than in front like the Exhibition. Take-up assemblies were available either belt or chain drive and changing where the magazine mounted meant that it did not move up and down with the framing mechanism which was how the Exhibition Model worked. This ad appears in the back of the 1912 edition of FH Richardson's Motion Picture Handbook and offered an Underwriters Model with arc rheostat for $225.

Both Exhibition and Underwriters Models were in production at the same time, with the Underwriters Model using a nickel-plated cast iron body versus the finger jointed oak case of the Exhibition Model. Late issue Exhibition machines and all Underwriters Models carried the nameplate and a license number of the Motion Picture Patents Company. The big difference between the two models is the use of a front shutter on all the later Underwriters machines. This front shutter made it necessary to mount the lower magazine underneath the base board, rather than in front like the Exhibition. Take-up assemblies were available either belt or chain drive and changing where the magazine mounted meant that it did not move up and down with the framing mechanism which was how the Exhibition Model worked. This ad appears in the back of the 1912 edition of FH Richardson's Motion Picture Handbook and offered an Underwriters Model with arc rheostat for $225.

Home Projecting Kinetoscope - ca 1911

Thomas Edison understood the value of the home market for his inventions, as shown by his 1878 Parlor Speaking Phonograph, which was introduced shortly after his original invention of the tinfoil phonograph in 1877. The Home Projecting Kinetoscope used an unusual 21mm format with three sets of images side by side and running in alternating directions. This allowed the film to be shown forward and backward in order to triple the running time while only having to be rewound at the end of every 3rd pass through. The Home Kinetoscope used a small arc lamp and was also able to show miniature Magic Lantern slides that were printed with 10 images on each glass plate. Here is Edison himself examining a Home Kinetoscope film with a projector sitting on its metal storage box on a table to the left.

Thomas Edison understood the value of the home market for his inventions, as shown by his 1878 Parlor Speaking Phonograph, which was introduced shortly after his original invention of the tinfoil phonograph in 1877. The Home Projecting Kinetoscope used an unusual 21mm format with three sets of images side by side and running in alternating directions. This allowed the film to be shown forward and backward in order to triple the running time while only having to be rewound at the end of every 3rd pass through. The Home Kinetoscope used a small arc lamp and was also able to show miniature Magic Lantern slides that were printed with 10 images on each glass plate. Here is Edison himself examining a Home Kinetoscope film with a projector sitting on its metal storage box on a table to the left.

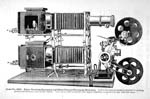

Kinetophone - 1913

Edison's "Talking Pictures" is most likely the source of the first popular use of the term "talkies" to refer to synchronized sound and film shows. An acoustical concert cylinder phonograph on stage was connected by a drive shaft to the projectors or "Kinetophones" at the back of the room. The films were only about 6 minutes long, due to the limitations of the running time of the phonograph records. The technical difficulty of mechanically linking a sound reproducing device to a movie projector would be encountered again a few years later with the Vitaphone sound on disc system and Western Electric Universal Base projectors.

Edison's "Talking Pictures" is most likely the source of the first popular use of the term "talkies" to refer to synchronized sound and film shows. An acoustical concert cylinder phonograph on stage was connected by a drive shaft to the projectors or "Kinetophones" at the back of the room. The films were only about 6 minutes long, due to the limitations of the running time of the phonograph records. The technical difficulty of mechanically linking a sound reproducing device to a movie projector would be encountered again a few years later with the Vitaphone sound on disc system and Western Electric Universal Base projectors.

Super Kinetoscope - 1916

While the Underwriters Model was basically just a makeover of the Exhibition Model which had become obsolete, the Super Kinetoscope was an entirely new design. Edwin S Porter helped develop the successful Simplex Standard projector which was introduced in 1911, and when he left Edison, bought shares in the Precision Machine Company that produced the machine. Nicholas Power had cut his teeth repairing Edison projectors and his Cameragraphs became the standard of the second generation of motion picture projectors beginning with his Model 6, which was introduced in 1909. Alva C Roebuck was selling his Optigraphs and Motiographs by mail order right along, and Edison was falling further and further behind. The Super Kinetoscope was too little too late and being too high priced to produce and sell, was quickly abandoned. This ad is from the back of the 1916 edition of FH Richardson's Motion Picture Handbook.

While the Underwriters Model was basically just a makeover of the Exhibition Model which had become obsolete, the Super Kinetoscope was an entirely new design. Edwin S Porter helped develop the successful Simplex Standard projector which was introduced in 1911, and when he left Edison, bought shares in the Precision Machine Company that produced the machine. Nicholas Power had cut his teeth repairing Edison projectors and his Cameragraphs became the standard of the second generation of motion picture projectors beginning with his Model 6, which was introduced in 1909. Alva C Roebuck was selling his Optigraphs and Motiographs by mail order right along, and Edison was falling further and further behind. The Super Kinetoscope was too little too late and being too high priced to produce and sell, was quickly abandoned. This ad is from the back of the 1916 edition of FH Richardson's Motion Picture Handbook.